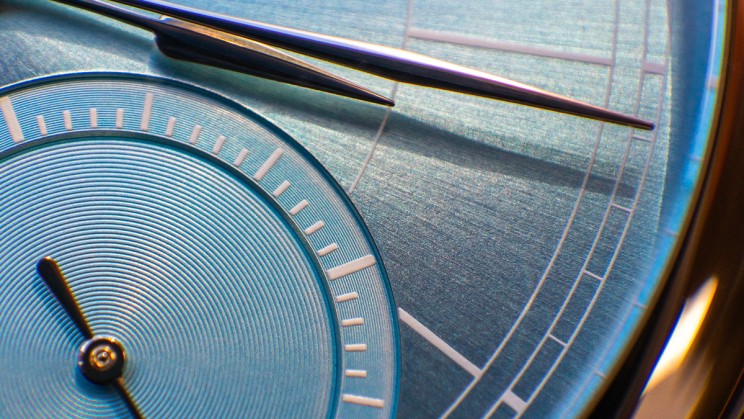

Since its founding nearly 15 years ago, Laurent Ferrier has become a byword for refined, neoclassical watchmaking thanks to immaculately executed models like its Classic Tourbillon Double Spiral and its Classic and Square Micro-Rotors.

A decade into its existence, the Geneva brand added another string to its bow when it presented the Grand Sport Tourbillon, its first integrated-bracelet sports watch, inspired by company co-founders Laurent Ferrier and François Servanin’s passion for motor racing: The pair have competed multiple times in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, even clinching third place in 1979.

Whether expressed through its exquisite dress timepieces or more assertively styled sports watches, recurring traits characterise the brand’s collection: A pure design replete with subtle details – the fruits of Ferrier’s four-decade experience at Patek Philippe where he was Head of Product Development; elegantly engineered movements conceived by Ferrier and his constructor son Christian in concert with external partners; top-notch chronometry; and the finest of hand-finishing.

Watchmaking Goodness

While the independent outfit now boasts five calibres, its second movement, the micro-rotor Calibre FBN229.01 unveiled in 2011, played a key role in cementing the brand’s place on the list of grail-worthy indies. Not least because it allowed for a more accessible price point compared to the company’s debut tourbillon movement, while still delivering a ton of watchmaking goodness.

To this day, the Classic and Square Micro-Rotors which house the Calibre FBN229.01 remain collector favourites. But what few people realise – even many of those now wearing them “in the wild” – is that it features a different kind of escapement compared to that found in most modern wristwatches: It has a “natural escapement”.

Lever Escapement

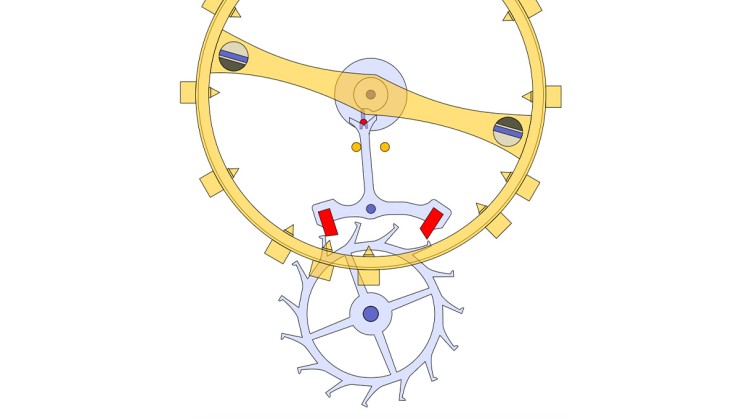

In mechanical watches, the escapement regulates the controlled release of energy from the mainspring to the gear train, ensuring accurate timekeeping and precise indications.

Most watches today feature the Swiss lever escapement because of its reliability, durability and ease of manufacture. The mechanism uses a lever with two pallets that lock and unlock the escape wheel, controlling the energy release to the balance wheel in precise impulses. However, this locking and unlocking process involves friction and energy loss, which can compromise precision. While lubricants can help to reduce friction, they can also degrade or clog over time."

Natural Escapement

Over a decade before he patented the tourbillon in 1801, the great Abraham-Louis Breguet recognised the downsides to the lever escapement and set about finding a low-friction, oil-free alternative.

The Neuchâtel native had probably noted how another escapement, the detent escapement, had managed to reduce friction and dispensed with the need for lubrication. This used a detent – a small spring-loaded arm – to lock and unlock the escape wheel, giving an impulse directly to the balance. But the detent escapement was delicate and susceptible to shocks.

So, Breguet devised the “natural escapement” combining the best of the lever and detent escapements. It featured two escape wheels whose lateral teeth meshed together while its vertical “pillars” locked and unlocked a central detent for a double direct impulse. It worked, but not quite well enough for the watchmaker to scale it – imprecise tolerances in the escape wheels could compromise the regularity of the impulse to the detent.

Picking Up Where Breguet Left Off

It wasn’t until two centuries later that watchmakers picked up Breguet’s idea and began bringing it to a successful conclusion. First, George Daniels developed a natural escapement using two separate gear trains for what would become his Space Traveller. Then, Derek Pratt employed an internal gear ring so his Double-Wheel Remontoir Tourbillon could benefit from such an escapement.

But both of these were sizeable pocket watches and it wasn’t until the Dual Direct Escapement used in 2001’s Ulysse Nardin Freak that the natural escapement found its way into a compact wristwatch, made possible in part thanks to the innovative use of silicon to make its two escape wheels.

An “Inspired” Movement

Fast forward to 2010, and Laurent Ferrier was contemplating the creation of the brand’s second calibre, eyeing a fitting follow-up to the Tourbillon Double Spiral which had won the prize for Best Men’s Watch at the Grand Prix d'Horlogerie de Genève that year.

In keeping with his penchant for classicism, he told his son Christian – formerly of Roger Dubuis and who would be working on the movement – that he was looking for a micro-rotor calibre with generous power reserve and strong chronometric performance. What’s more, it had to be “inspired” adding something of substance to the contemporary watchmaking landscape. Why not, he suggested, try fitting it with a natural escapement?

After all, since the Freak a decade previously, little to nothing had been developed in the watch world in terms of the natural escapement, and with good reason.

“The natural escapement isn’t like a tourbillon, where you can draw on a multitude of precedents and designs to develop your own one,” says Basile Monnin, now Head of Watchmaking at Laurent Ferrier and a member of the brand’s watchmaking team at the time.

He continues: “The natural escapement might just be a few wheels that help bring the impulse directly to the balance without going through the pallet fork, but there are virtually no models for that. There are some sketches and stories of things that have been done before, but essentially, it's a novelty. So, we had little to work off of, making it as difficult to develop as a major complication.”

Design, Materials and Execution

Supported by Enrico Barbasini and Michel Navas of La Fabrique du Temps, the brand devised a natural escapement entailing specific geometries that built on Breguet’s concept. It had two escape wheels each featuring vertical pillars and a central detent arm that rocks left and right to interact with an impulse pallet to provide a double impulse to a 3Hz screwed balance fitted with Breguet overcoil hairspring. Later, a safety pin was added to provide shock resistance.

But for the system to work, the watchmaker had to find the right materials to make the escape wheels and detent arm.

“Lever escapement escape wheel are two-dimensional,” says Monnin. “Our escape wheels are three-dimensional with complex geometries that you can't machine in a traditional way. And they need to be accurate to the micron, otherwise they won't work.”

Exploring different materials and geometries, the brand eventually decided to avail of LIGA (Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung) – a micro-precision moulding process – using it to make the escape wheels from nickel phosphorus.

The detent arm and impulse pallet proved equally hard to perfect.

“We first tried making these in gold, and then ruby, but we just couldn't get the right results,” says Monnin. “We found the best solution to be silicon, made using deep reactive-ion etching (DRIE). Silicon’s self-lubricating properties work well with the nickel phosphorus escape wheels.”

He adds: “The only limit Breguet had was technology. Such precision processing and material technologies didn't exist in his day. If he'd had access to LIGA and DRIE, I think he definitely would have used these just to be able to make the idea in his head work.”

Less Lubrication and Stable Rate

In the end, Laurent Ferrier’s natural escapement does exactly what it is supposed to do: Reduce the need for lubrication and improve timekeeping precision.

“Our natural escapement doesn’t need oil or grease, except at the pivot points of the axes,” says Monnin. “And it consumes so little energy that we keep the same amplitude for almost the entire 72-hour power reserve of the movement. And if we keep the same amplitude, that means we keep the same rate. It brings a remarkable consistency.”

“All our movements are adjusted to six positions, which is not necessarily the case for all manufactures. For logistical reasons, we don't send the movements to COSC, but they would easily pass it, even surpass it.”

Arguably, the proof is in the actual wearing, and this natural escapement has shown itself to be more than robust since deliveries of the Laurent Ferrier Micro-Rotor began over a decade ago.

“We’ve found that the escapement holds up extremely well,” says Monnin. “It’s not fragile, even if in the user manual we do advise customers to err on the side of caution in how they use their watch.

He adds: “We have delivered a significant number of pieces and are not inundated with after-sales issues. Say, after five years, when customers return their watch for servicing, often the case is worn, but the movement works fine. Some clients are even regular golfers who wear their watch while playing. The longevity of the product proves that it is reliable.”

Rare Skill

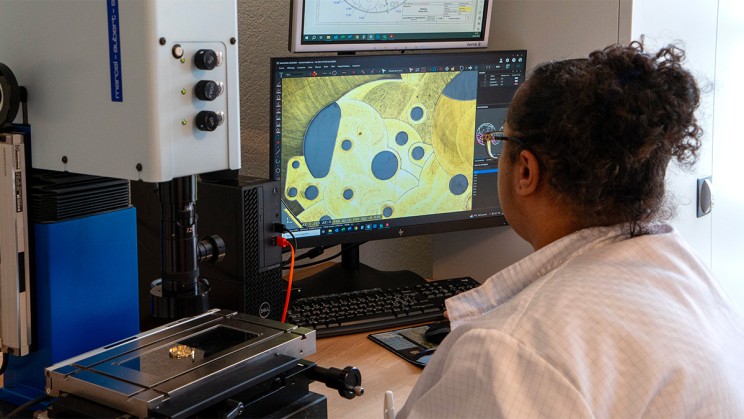

It’s not just the design, materials and execution of this natural escapement that make it a success. Also crucial is the skill of Laurent Ferrier’s watchmakers when it comes to the assembly, regulation and testing of Calibre FBN229.01.

“Most watchmakers, even those with 20 years’ experience who have worked on minute repeaters, will never have had the chance to work on a natural escapement,” says Monnin. “So there's a lot of training involved and a number of rules to follow in order to make the escapement work properly.”

The brand’s watchmakers have even had to find a way to correctly decipher the results given by a Witschi machine, the device watchmakers – and even some retailers, distributors and customers – use to analyse rate, amplitude and beat error.

“Because there's a double direct impulse, the machines don't really understand what they detect,” says Monnin. “At first, it can be a bit confusing because the person reading the Witschi print-out just sees dots everywhere, not a perfect line. They don’t understand where the real dots are.

He continues: “So, we have learned to interpret and make sense of what we read on the Witschi machine. And we have even trained up watchmakers in local markets so that they are able to do the same.”

Technical and Aesthetic Tour de Force

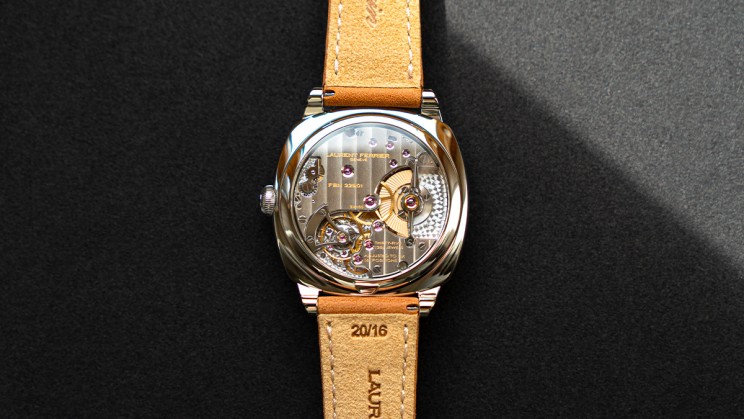

It shouldn’t be forgotten, of course, that this natural escapement is just one element of a movement that that is both a technical and aesthetic tour de force. In fact, the escapement’s efficiency is such that the moment of torque required to wind the mainspring is reduced, helping to optimise the unidirectional winding. Plus, the barrel is placed on rubies for low-friction turning.

Other features, too, enhance the action of the micro-rotor including the use of a pawl rather than a noisy ball-bearing system. And the gold micro-rotor is mounted on its axis between two O-rings for a silent block-style shock protection.

All these elements, plus a carefully chosen mainspring, help to contribute to a “weekend proof” three-day power reserve over the course of which timekeeping precision remains impressively constant thanks to the natural escapement.

Finest of Hand-Finishing

Finally, it would be remiss of us not to mention the supreme level of hand-finishing on the Calibre FBN229.01 of the Laurent Ferrier Micro-Rotor models.

The edges of its bridges are bevelled and polished by hand, while their surfaces are decorated with Geneva waves. The spokes of the gears are bevelled too, and the screw heads and jewel countersinks are, of course, polished. The surfaces of steel parts like the balance cock are black polished by hand. Perlage (spotting), straight graining and circular graining are also deployed to excellent effect.

To give an idea of Laurent Ferrier’s dedication to traditional hand-decoration, it takes two full days just to hand-finish the balance cock.

We’ve heard that there is still more to come from Laurent Ferrier, its Calibre FBN229.01 and its Micro-Rotor editions, so stay tuned for some exciting news later this summer!

To learn more about Laurent Ferrier, please visit the brand’s website.