Guilloché is under pressure. This venerable finishing technique, popularized by Breguet 250 years ago, is now widely copied—especially by machines (CNC or computer numerical control machines that follow programmed instructions) and by increasingly sophisticated processes like FEMTO laser engraving.

A Triple Threat

As a result, traditional guilloché is becoming increasingly rare, for three main reasons. First: There is a shortage of skilled artisans. Guilloché training programs have become almost non-existent. The skill is now only passed down from master to apprentice, one-on-one, which drastically reduces the number of new guillocheurs entering the job market each year.

Second: It takes at least three years for a guillocheur to become autonomous and versatile. This kind of time investment is typical in artisanal trades, but again, it puts pressure on the availability of talent.

Third: Traditional guilloché machines are, on average, a century old. They are extremely rare on the second-hand market and often spark fierce bidding wars between brands willing to pay top dollar. So, not only are there few apprentices—but there are even fewer machines on which they can train.

Breguet, Guardian of the Craft

Abraham-Louis Breguet largely defined the techniques and uses of guilloché. The legendary watchmaker quickly understood its triple advantage: protecting the dial, decoration, and enhancing readability. His use of guilloché can be traced back to as early as 1786. A good example is found in his perpetual repeater watch No. 46 from 1787. It already shows the master's aesthetic signature: three dial zones, each with its own guilloché pattern. This zoning approach is still used today, particularly in the Breguet Classique Chronométrie 7727.

The Most Famous Patterns

There are as many guilloché patterns as there are creative minds to invent them—in other words, an infinity. That said, a few classics have stood the test of time. Among them are the Clou de Paris (small conical shapes) and Grain d’Orge (oblong shapes), the best known. Breguet has developed many, but does not own a specific “Breguet motif” per se.

Modern Patterns

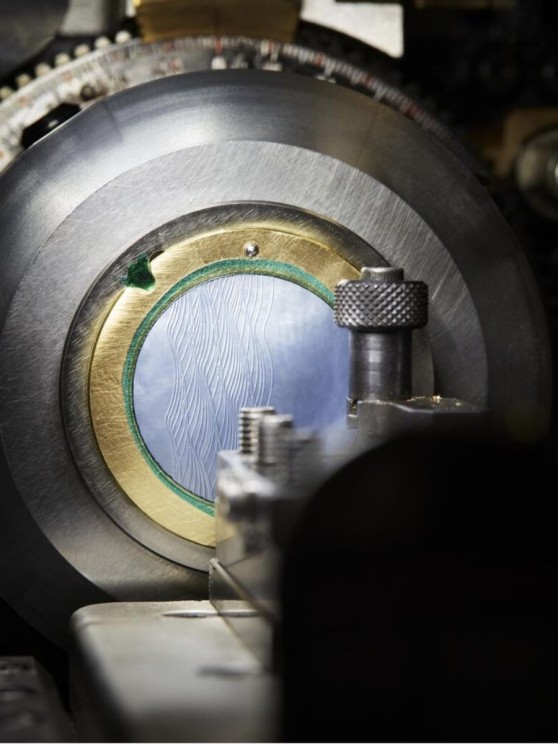

Breguet continues to invent new patterns regularly, just as Abraham-Louis Breguet would have. The recent Marine Tourbillon Équation Marchante 5887, for example, features a wave motif evoking its maritime roots.

Forgotten Patterns

Many of the timepieces held at the Breguet Museum (Place Vendôme, Paris) and in other museums around the world reveal the stylistic diversity of motifs from Breguet and his successors. Some patterns are no longer in use, such as the unusual dial on Breguet No. 92, featuring a granulated / dotted motif that has never been replicated. In the Art Deco era, the Brown family—then owners of Breguet—experimented with two-tone guilloché designs that were more or less successful, but certainly reflected the fashion of the time. It seems that in the modern era, Breguet has not revisited this particular chromatic style.

The brand’s archives form an almost inexhaustible documentary collection that will no doubt continue to inspire new creative directions for the living art of guilloché—especially as Breguet celebrates its 250th anniversary.